When Justice Costs $15 a Day: The Hidden Price of America’s Jury System

By: Truth Behing The Bars

We talk a lot about justice in America — but not enough about the people who are supposed to deliver it: the jurors.

They are the backbone of our legal system, yet many are barely compensated enough to buy lunch.

In Florida, jurors earn just $15 a day for the first three days — only if their employer doesn’t pay them — and $30 a day after that.

No mileage. No food. No childcare.

And yet, these are the people deciding whether another human being walks free or spends life in a cell.

The Broken Balance of Justice

Florida is one of the toughest states in the country when it comes to punishment:

🔒 Highest number of people serving life without parole (LWOP) — around 11,000.

⚰️ Active death row and an increase in executions in 2025.

👥 Broad felony-murder law that punishes even those who never killed anyone.

🚔 One of the highest incarceration rates nationwide.

That’s not coincidence — that’s a culture of speed, pressure, and imbalance in the courtroom.

When jurors can’t afford to be there, justice bends toward whoever can stay the longest.

The Financial Stress of Being a Juror

Most Americans live paycheck to paycheck. When they get a jury summons, their first thought isn’t “civic duty” — it’s “can I afford this?”

Missing a week of work means missed rent, lost childcare, or risking your job.

So people beg to be excused, leaving behind only those who can afford it: retirees, government workers, or the wealthy.

The people most affected by the justice system — working-class families, single parents, and people of color — are often the ones priced out of participation.

In Palm Beach County, Florida, there’s no local law requiring employers to pay jurors during service, meaning most residents who serve do so unpaid.

One Palm Beach juror told the Palm Beach Post, “With employers reluctant to pay, people here just can’t afford to serve.”

The Science of Financial Anxiety

When you’re worried about bills, your brain literally has less room to think.

A Princeton University study found that financial stress can reduce mental performance by up to 13 IQ points — the equivalent of losing an entire night’s sleep.

So imagine sitting on a jury, expected to weigh evidence, recall testimony, and argue with eleven strangers — all while worrying about your light bill.

That’s not impartiality — that’s survival mode.

This is why jurors often “rush to finish.”

It’s not because they don’t care — it’s because they can’t afford to care longer.

And when justice is rushed, truth gets buried.

Voices from Real Jurors

From Reddit and local forums, angry and discouraged jurors across the country — especially in Florida — have spoken out:

“My job didn’t pay me :(” — Reddit user, Florida 【reddit.com/r/florida】

“It sucks. You show up at 7 am, just to be called in at 12 pm. I lost two days’ pay.” — Reddit user, Florida

“People are being railroaded into jail out of revenge by juries who are comprised of bitter, angry people.” — Reddit, Florida thread

“They pay you five dollars a day here in Mississippi. You lose more in gas.”

“I served on a trial in Texas — $6 a day. I wanted to do my civic duty, but I was literally worried about groceries the whole time.”

“I did jury duty in Palm Beach years ago. Took the bus, lost tips from my job, and ended up spending more than I made. Never again.”

The frustration is universal: jurors want to serve, but the system makes them resentful, distracted, and financially strained.

The Florida Example in Numbers

Category Florida Low-Pay States (TX, MS) Higher-Pay States (CA, NY) Juror Pay $15/day (days 1–3), $30/day after $5–6/day $50–$72/day Incarceration Rate Among the highest in U.S. Very high Lower to moderate LWOP Population ~11,000 Thousands Significantly lower Death Penalty Active Active Abolished Exonerations Top 5 in U.S. Moderate High (more review systems)

🧾 Source: Florida Stat. § 40.24, The Sentencing Project, Prison Policy Initiative, National Registry of Exonerations.

Florida has one of the lowest juror pay scales — and one of the harshest sentencing systems.

When jurors are financially anxious and overworked, verdicts trend toward “wrap it up,” not “prove it beyond a reasonable doubt.”

What the Data Looks Like

Florida’s Incarceration Rate Over Time

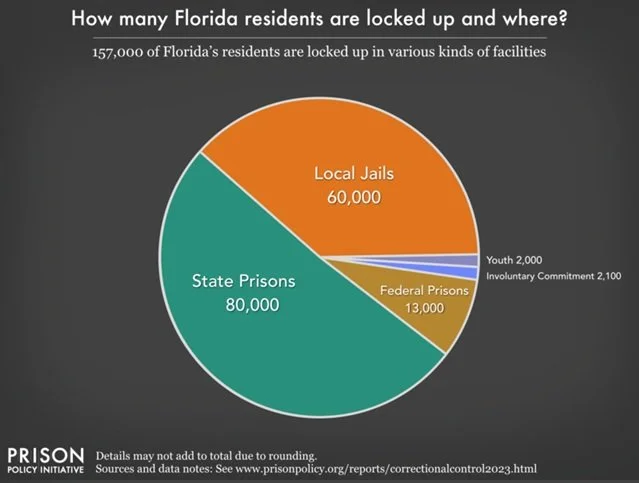

Florida’s Locked-Up Population by Type

Racial Disparities in Incarceration

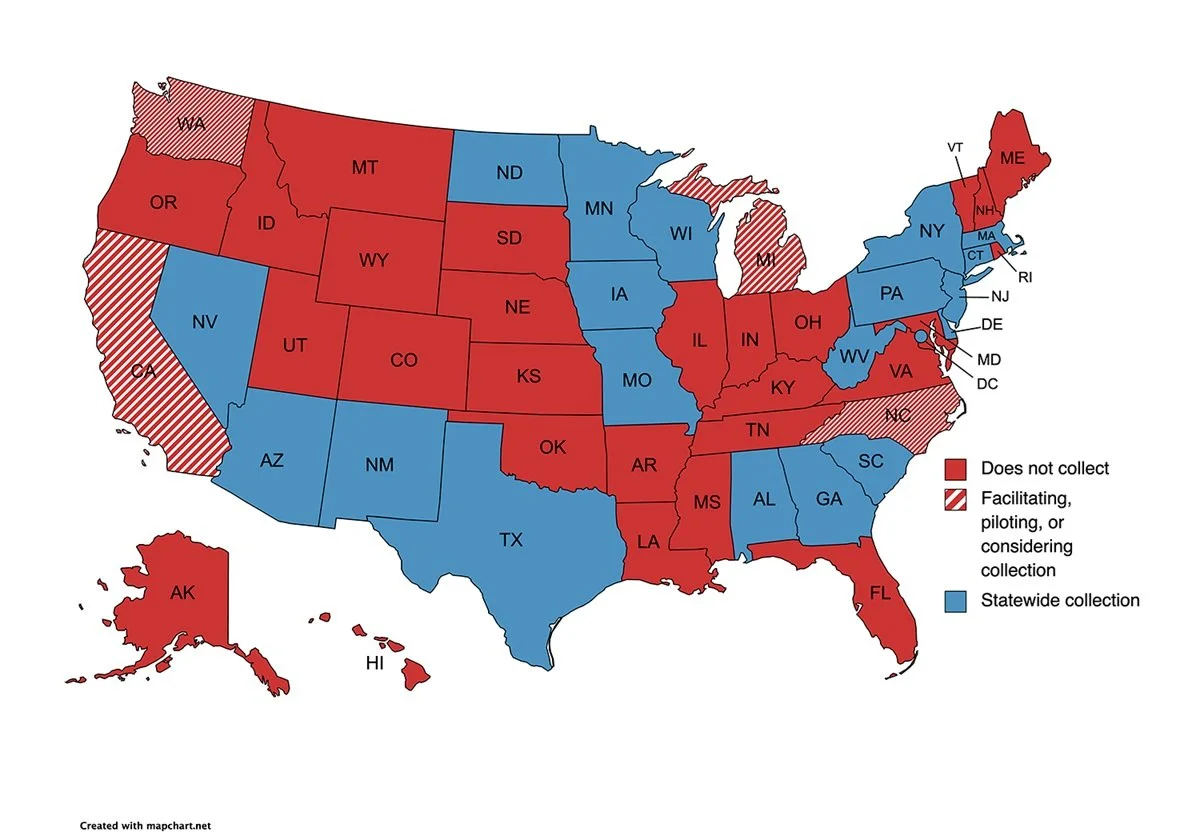

Jury Pay Map (By State)

Each of these charts tells the same story:

Florida punishes more, pays less, and risks more injustice than nearly any other state.

The Federal Principle That States Keep Ignoring

The Sixth Amendment guarantees every American the right to an impartial jury.

But how impartial can you be if your stomach is in knots over missed wages and unpaid bills?

Under federal due-process standards, jurors must be competent and unbiased.

Yet states like Florida routinely seat jurors under financial duress — people who can’t focus, who want out, who are silently panicking about how they’ll make rent.

That’s not just unfair — it’s unconstitutional in spirit, if not yet in statute.

Proof That Paying Jurors Works

San Francisco’s Be the Jury pilot program raised juror pay to $100 per day for low-income participants.

The outcome?

81% said they could finally afford to serve.

Juries became more diverse and representative.

Participants reported feeling proud to serve.

If one city can afford to pay jurors decently, what’s Florida’s excuse — with its billion-dollar prison budget and private contract kickbacks?

The Ripple Effect

Every rushed deliberation, every juror who said “let’s just get this over with,” adds up.

It adds up to wrongful convictions, life sentences, and families destroyed.

It’s easy to blame the system — but the system is people.

When those people are overworked, underpaid, and under stress, the system’s outcomes will always reflect that.

Real Solutions

If we want fair trials, we need fair juries. That means:

Raise juror pay — peg it to local minimum wage or a percentage of average daily income.

Create hardship stipends — rent, childcare, or food assistance for jurors below certain income levels.

Guarantee paid jury leave — require employers to continue pay (with tax credits).

Train judges to recognize economic bias — financial stress should qualify as hardship for excusal or deferral.

Protect the cross-section ideal — no one should be excluded from civic duty because they can’t afford it.

❤️ Justice Shouldn’t Depend on Who Can Afford to Serve

If we want verdicts based on truth, not time, then we must remove the financial barriers that warp our juries.

Every trial, every life, every sentence deserves the full attention of an uncompromised mind — not one preoccupied by overdue bills.

America spends billions locking people up.

Maybe it’s time to spend a little ensuring the right people stay free.

📢 Share this if you believe justice should never come at a $15-a-day price tag.

#JusticeReform #JuryDuty #Florida #PalmBeach #TruthBehindTheBars #FairTrialsMatter

Would you like me to now make a shorter version optimized for Change.org (petition or campaign description under 400 words, plus a headline and taglines)? It would carry the same emotional tone but more “action-focused.”

Intimate Encounters for Safer Prisons: How Conjugal Visits Can Bring Humanity and Revenue to Florida

By Truth Behind The Bars

Introduction

Florida’s prisons are in crisis — plagued by violence, neglect, and an erosion of humanity. Inmates live under unbearable heat, overcrowded conditions, and emotional deprivation, while officers face daily danger in an environment fueled by tension and hopelessness.

Yet a simple, humane reform could change everything: allowing structured, supervised intimacy visits for eligible inmates and their partners. Far from being a “luxury,” these visits could become one of Florida’s most effective behavioral and safety tools — reducing violence, restoring dignity, and generating millions in revenue for much-needed facility improvements.

Florida’s Prisons: A Crisis of Violence, Neglect, and Silence

Florida’s correctional system has reached a breaking point. In just 2025 alone, the state has faced a wave of assaults, deaths, and abuse scandals — incidents documented by The Miami Herald, Local10 News, and Florida Phoenix. At least a dozen major cases have made headlines this year, and countless others go unreported, buried in weekly FDOC “assault advisories.”

Each violent outbreak represents a failure to meet inmates’ psychological and emotional needs. A system built solely on punishment and deprivation breeds anger and chaos — not rehabilitation. Programs like Intimacy Visits would not only reconnect inmates with their partners and families, but also give them a reason to behave, to hope, and to remain human.

Violent and Negligent Incidents Reported in Florida Prisons (2025)

March 17 – Cross City Correctional Institution: Inmate died; family demanded answers. WCJB News

March 4 – South Bay Correctional Facility: Inmate accused of strangling another inmate over a drug dispute. CBS12 News

April 25 – Federal Correctional Institution Marianna: Federal inmate killed by another inmate. Tallahassee Democrat

August 14 – Dade Correctional Institution: Seven correctional officers charged for beating a handcuffed inmate and attempting a cover-up. Local10 News

September 18 – Florida State Prison: Inmate Kwamane Silas assaulted a correctional officer by kicking them. FDOC Advisory

September 11 – Florida State Prison: Inmate Christian Quispe struck a correctional officer during an altercation. FDOC Advisory

Statewide – Ongoing: FDOC’s weekly Assault Advisories report dozens of inmate-on-staff and inmate-on-inmate assaults each week. FDOC Newsroom

August – Extreme Heat Reports: Violence and medical emergencies increase during heat waves. WUSF News

January – Statewide: “Prison abuse, deaths, and escapes prompt calls for more oversight.” Florida Phoenix

2025 – Statewide: FDOC releases new database revealing dozens of unexplained inmate deaths. Florida Justice Institute

These are just a few of the countless incidents that have surfaced — a small window into what happens every week behind Florida’s prison walls. When testosterone runs high and tempers flare in an environment stripped of intimacy, compassion, and human connection, violence becomes inevitable.

The Biology and Psychology of Connection: Why Both Men and Women Need Intimacy to Stay Human

Inside Florida’s prisons, tension and deprivation build daily — not just from confinement, but from the loss of basic human touch and emotional connection. For both men and women, the absence of intimacy creates a psychological pressure cooker that fuels aggression, despair, and hopelessness.

Science makes the link clear: testosterone, cortisol, dopamine, and oxytocin — the body’s regulators of stress and bonding — all respond to touch, affection, and connection. When those needs are unmet, the mind and body react.

For men, unreleased testosterone combined with chronic stress increases irritability, impulsivity, and aggression. Studies in Hormones and Behavior and Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews confirm that elevated testosterone without outlets can heighten dominance struggles and violent outbursts — a direct contributor to prison violence.

For women, deprivation can be just as damaging. Research in Health and Justice Journal (2021) found that incarcerated women — many of whom have histories of trauma or abuse — experience heightened anxiety and depression when isolated from family or physical contact. Regular, meaningful connection reduces infractions, self-harm, and emotional instability.

The human body is wired for connection. When deprived of affection or closeness, testosterone becomes volatile, cortisol rises, and emotional control breaks down. But when people are allowed structured, safe, and consensual intimacy, the brain releases oxytocin and endorphins, natural chemicals that calm the body, lower stress, and increase empathy.

Whether it’s a parent embracing their adult child or a partner reconnecting after years of distance, these moments restore accountability and humanity — transforming prisons from war zones into environments where peace has a fighting chance.

Behavioral Impact: The Psychology of Anticipation and Reward

When an inmate knows they have something to look forward to — especially a visit from someone they love — their entire mindset changes. They become careful not to fight, argue, or risk losing their visitation privileges. It’s not just a visit; it’s their lifeline to the outside world.

As psychologist Dr. Craig Haney observed, “When a person in confinement has even one healthy, emotional connection to anticipate, the incentive to behave increases dramatically.”

Intimacy Visits extend that incentive. They become a reward earned through good behavior, giving inmates self-control, focus, and an emotional outlet. When inmates behave well to protect something meaningful, prison culture itself begins to shift.

Program Design: The Florida Intimacy Visit Proposal

Eligibility & Rules:

Visitor must be on the inmate’s approved visitation list for at least one year.

Only one approved visitor at a time; name may be changed once per year after review.

Inmate participation is voluntary.

Excluded: sexual predators, rapists, serial killers, and cannibals.

Included: inmates serving long sentences or life without parole (LWOP) who maintain good conduct.

Visit Structure & Safety:

Duration: 50 minutes, plus 10 minutes for cleaning.

Fee: $200 per visit (paid by visitor).

Rooms include clean bedding and condoms.

No locked doors; panic-string alarm installed for emergencies.

Monitored by 1 guard per 2 trailers (each trailer has 2 private rooms).

Only a small radio allowed, with pre-approved playlists.

Schedule:

Visits available 3 days per week (Thurs–Sat or Fri–Sun depending on facility).

Some prisons may open 4 days based on security classification.

Revenue Projection: A Self-Funding Path to Safety and Humanity

With roughly 50 major state prisons, here’s what the math looks like:

Option A: 4 trailers per prison (8 rooms)

$200 × 4 sessions/day × 8 rooms × 3 days/week = $19,200 per week per prison

Annual total per prison ≈ $1 million

Statewide annual revenue: ≈ $50 million

Option B: 8 trailers per prison (16 rooms)

$200 × 4 sessions/day × 16 rooms × 3 days/week = $38,400 per week per prison

Annual total per prison ≈ $2 million

Statewide annual revenue: ≈ $100 million

Every dollar can be deposited into a “Facility Well-Being & Infrastructure Fund” to pay for air conditioning, safety upgrades, and staff training — directly improving Florida’s most dangerous prisons without burdening taxpayers.

Scientific References & Supporting Research

Dabbs, J. M., & Morris, R. (1990). Testosterone, social class, and antisocial behavior in men. Social Psychology Quarterly, 53(4), 333–340.

Archer, J. (2006). Testosterone and human aggression: An evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(3), 319–345.

Carré, J. M., & Olmstead, N. A. (2015). Social neuroendocrinology of human aggression: Examining the role of testosterone. Hormones and Behavior, 70, 21–32.

Health & Justice Journal (2021). Trauma histories and behavioral health of incarcerated women.

Prison Policy Initiative (2021). Family contact during incarceration reduces misconduct and recidivism.

Haney, C. (2003). The Psychological Impact of Incarceration. U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services.

Frontiers in Psychology (2016). Affectionate touch and social bonding: Physiological correlates of reduced stress and aggression.

Closing Message

Florida’s prisons don’t need harsher policies — they need smarter ones. When testosterone runs high and hope runs low, tempers explode. But when inmates are given something to look forward to, something human to protect, violence drops and safety rises.

Intimacy visits are not about indulgence — they are about prevention, rehabilitation, and common sense. They are about turning a system built on punishment into one that finally understands people can change — when given the chance to feel human again.

Would you like me to now create your matching Change.org campaign page using this exact tone and information (headline, summary, key bullet points, and hashtags)? It’ll be ready to copy and paste into your petition launch form.

Join us to make a change Bring Intimacy Visits to Florida Prisons - Save Lives and Generate Millions in Revenue @ CHANGE.org

Mandatory Minimums & Life Without Parole in Florida: Why We Must Challenge Them

By Truth Behind the Bars

The Promise vs. The Reality

In theory, sentencing in America should balance punishment with fairness. Judges are supposed to consider whether someone is a first-time offender, a young adult, or a minor participant in a crime. But in Florida, that balance is broken.

Florida’s mandatory minimums and life without parole (LWOP) laws strip away judicial discretion, forcing courts to impose the harshest possible penalties — often on people with no prior record.

Florida now holds over 10,000 people serving LWOP, more than any other state in the country.

What Should Happen to First-Time Offenders?

Across the U.S., most states recognize that first-time offenders deserve a second chance:

Federal courts: First-time offenders score lowest on the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines. Nonviolent first-timers may qualify for probation, community service, or the safety valve to avoid mandatory minimums.

Georgia: Has a First Offender Act allowing many to plead guilty, complete probation, and avoid a conviction record (serious violent felonies excluded).

California: Offers diversion for some misdemeanors and drug cases.

Alaska: The only state that does not allow LWOP at all — all life sentences have parole eligibility.

But in Florida, there is no broad first-offender statute. A 18-year-old first-timer caught up in a felony-murder (that did not commit the murder) case is treated the same as a hardened repeat offender.

Florida’s Mandatory Minimums and LWOP

Florida’s laws are among the harshest in the nation:

Mandatory LWOP for felony murder: If someone dies during a felony (robbery, burglary, etc.), all participants can be sentenced to LWOP — even if they didn’t kill anyone. (Ex. Ryan Holle)

No parole: Florida abolished parole in 1995. Life means life.

10-20-Life law: Gun involvement brings mandatory add-on years (10, 20, or 25-to-life), even if no one is shot.

This is how Florida built one of the largest life-sentenced populations in the world.

🌟Ryan Holle was convicted under Florida’s felony murder rule after he lent his car to a friend, who drove off with others and committed a burglary during which a woman was killed — even though Holle was physically miles away, asleep, and never pulled the trigger. He received life without parole, the same sentence as the actual killer and co-defendants, despite his more peripheral involvement. In 2015, his life sentence was commuted by Governor Rick Scott to 25 years, and he was released in 2024 after serving much of that time.

Tampa Bay 28 (WFTS)+3Wikipedia+3Tampa Bay 28 (WFTS)+3

24-7 Press Release+3Tampa Bay 28 (WFTS)+3Wikipedia+3

Who Is Fighting Back in Florida?

Baxter v. Florida DOC – A man sentenced to LWOP under felony murder despite being far removed from the actual killing is challenging the statute’s fairness.

Juvenile & youthful offender cases – After Graham v. Florida (2010), LWOP for juveniles in non-homicide cases was struck down. In 2024, Massachusetts went further, banning LWOP for 18–20 year-olds. Michigan has also limited mandatory LWOP for that age group. Florida has not.

Amicus briefs – Groups like The Sentencing Project and FAMM have filed “friend of the court” briefs in Florida cases, arguing that mandatory LWOP violates constitutional proportionality and global human rights norms.

What Is an Amicus Brief?

Amicus curiae means “friend of the court.”

An amicus brief is a legal filing by someone who is not a party to the case but who has expertise or a strong interest in the issue.

They provide data, history, and policy arguments the parties may not include.

They show judges the wider consequences of their decision.

They’re often filed by advocacy groups, academics, or even government agencies.

What’s Happening in Other States?

Florida is falling behind. Across the country, reforms are happening:

Massachusetts (2024): Banned LWOP for 18–20-year-olds (Commonwealth v. Mattis).

Michigan (2023–2024): Struck down mandatory LWOP for ages 18–20; judges must now review each case individually.

California: Expanded parole eligibility and created more resentencing opportunities.

Pennsylvania & Louisiana: Still impose mandatory LWOP for felony murder — but face increasing challenges.

Alaska: No LWOP at all, proving extreme punishment is not necessary for public safety.

By the Numbers – LWOP in the U.S.

Top States by LWOP Population (2024 census):

Florida – 10,915

California – 5,111

Pennsylvania – 5,059

Louisiana – 3,900

Michigan – 3,551

These five states account for nearly half of all LWOP cases in the U.S.

Truth Behind the Bars: Why This Matters

Florida’s sentencing scheme means:

First-time offenders can die in prison.

Young adults are treated no differently than the actual killer.

Rehabilitation and redemption are denied by law.

Mandatory minimums and LWOP don’t make us safer — they make us less just.

That’s why we fight to expose these cases and demand change. Through public education, coalition work, and tools like amicus briefs, we can push Florida to catch up with the rest of the nation.

Because injustice doesn’t end at sentencing. It lives inside the bars.

The Human Cost: Families Torn Apart, Tax Dollars Wasted

Every person sentenced under Florida’s mandatory minimums or LWOP laws isn’t just a number — they are someone’s son, daughter, brother, sister, mother, or father.

When Florida condemns first-time offenders to die in prison, it also condemns their families to a life sentence of loss:

Children grow up without parents.

Parents live their final years without ever hugging their child outside a prison wall.

Families scrape together money for phone calls, commissary, and endless legal fees, all while enduring the shame and stigma society places on them.

And the burden doesn’t stop with families. It falls on every Floridian’s shoulders.

Housing a single person in prison costs taxpayers tens of thousands of dollars each year.

When that person is sentenced to LWOP, the bill runs into the millions over a lifetime.

All for someone who, in many cases, was a first-time offender, never pulled a trigger, or was barely an adult when they made a mistake.

This is not justice. It is waste.

Where is the humanity in locking away someone forever without considering their potential to change? Where is the mercy in treating a teenager who made a bad choice the same as a career killer? Where is the wisdom in draining tax dollars to warehouse people who pose no future threat?

Florida’s sentencing laws claim to protect society, but in reality, they destroy families, waste resources, and ignore redemption.

If justice has no room for humanity, then what kind of society are we building?

Here’s what the data shows — and what remains uncertain — about how much Florida spends on inmates, especially those serving LWOP:

What We Do Know

Annual cost per inmate

According to the Florida Legislature’s “Criminal Justice Impact Conference,” in FY 2021–22 the full operating cost per inmate in state facilities was $74.44 per day, i.e. about $27,171 per year (excluding some debt service or indirect costs). (Econ Demographics Office)

More recent projections show rising costs: by FY 2024–25, the per-inmate cost is forecast at roughly $30,316 per year in operating costs. (Econ Demographics Office)

Note: these “full operating costs” include security operations, health services, and educational services. They do not include “debt service costs” (e.g. construction financing) or certain overhead/administrative burdens. (Econ Demographics Office)

State corrections budget & trends

Florida’s Department of Corrections is one of the largest state agencies; over time, even when the prison population has fallen, the DOC budget has grown. (Florida Policy Institute)

In 2017–18, Florida’s DOC budget was about $2.4 billion, with estimated cost to house an inmate then at $21,743 per year. (OPPAGA)

According to The Marshall Project, Florida spent over $300 million in one year to house prisoners serving life sentences (including LWOP). (The Marshall Project)

Florida’s prison infrastructure is old and decaying; independent reports estimate that repairs and modernization will cost billions (between $6.3 billion and $11.8 billion) over time. (Axios)

The Gaps & What We Don’t Know

We don't have a public breakdown of how much is spent specifically on LWOP inmates vs. non-LWOP inmates.

The full lifetime cost (i.e., over decades) per person serving LWOP is rarely calculated in state budgets — most figures stop at annual costs.

Overhead, capital expenditures, deferred maintenance, and healthcare for aging incarcerated people often fall outside the “operating cost” line items and aren’t always transparent.

What This Means: The Reality Behind the Numbers

Florida is spending tens (even hundreds) of millions annually just to maintain its LWOP population.

Because life-sentenced inmates never leave, their cumulative cost is enormous over decades — money that could have gone to schools, health care, infrastructure, or reentry programs.

The fact that per-inmate cost is rising even as the population falls shows that fixed costs (staff, facilities, systems) dominate — incarcerating someone forever is expensive whether you have 1 or 10,000 more inmates.

The Price of Injustice: What Florida Really Pays

For example, consider one actual inmate in Florida. At 18 years old, in 2007, a first-time offender made a mistake that lasted just two minutes. No one was harmed inside the store, no shots were fired, and no life was lost at the scene.

A year before Trial 1, a civil jury found the store owner — who initiated a high-speed chase — negligent. Expert testimony from Mr. Bopp confirmed the pursuit was an independent act that caused the fatal crash. This finding should have carried weight in the criminal case, but it was suppressed.

Then, in Trial 1, the judge granted a motion for judgment of acquittal on the premeditated murder theory of Count 1. By law, that ruling should have barred the State from retrying him on the same death under a different theory. But prosecutors ignored these protections, violating double jeopardy and collateral estoppel.

The outcome: after repeated prosecutions, the young man was sentenced to life without parole, despite being a non-shooter, first-time offender and a CPC score of 15.4years. He has now been imprisoned for more than 17 years — condemned to die in prison under laws that ignore both justice and truth.

Here’s what that costs you, the taxpayer:

Florida spends about $30,000 per year to house each inmate.

Over 10 years, that’s about $300,000.

Over 30 years, more than $900,000.

If he lives to age 70, the state will spend $1.5–$2 million just to keep him in prison.

And for what? A first-time offender who never pulled the trigger, convicted under laws the rest of the world considers outdated and unjust.

Now multiply that by the 10,000+ people serving LWOP in Florida. We’re talking billions of tax dollars poured into locking people away forever — money that could be invested in schools, healthcare, mental health treatment, victim services, and community safety programs that actually work.

The truth is clear: Florida’s LWOP system isn’t just unjust — it’s fiscally reckless.

Where is the humanity in condemning someone for life for a two-minute mistake as a teenager? Where is the wisdom in wasting millions to keep first-time offenders locked away forever?

This is not justice. This is cruelty, and we are all paying the price.

Why “Crackdowns” on Teens Won’t End Street Racing. But Tech and Industry Rules Could

By Truth Behind the Bars

We hear it after every tragic crash: “We’re getting tough to stop street racing.” But the playbook is always the same—steeper charges, bigger fines, longer suspensions—aimed primarily at young drivers. Meanwhile, the car market glorifies speed, and ALL new vehicles are engineered to blow past any legal limit you’ll see on U.S. roads.

The reality on the road

Speed kills; consistently. In 2023, 29% of U.S. traffic deaths were speeding-related; 11,775 people died. That’s not a niche problem; it’s a national one. (CrashStats)

The fastest posted speed limit in the U.S. is 85 mph (TX SH-130, Segments 5 & 6). Almost everywhere else tops out at 70–80 mph. So no, there aren’t legal roads for 120 mph joyrides. Yet cars routinely ship with top speeds far beyond that. (SH 130)

Enforcement only policies haven’t solved it. Even with post-pandemic attention, the U.S. still records tens of thousands of deaths per year; 2024 deaths dipped but remain elevated vs. pre-2020. (Reuters)

How states respond today (example: Florida)

Florida’s “racing on highways” statute makes first-offense racing a first-degree misdemeanor, with license revocation and escalating penalties for repeat offenses. Serious consequences that fall squarely on (often young) drivers. (The Florida Senate)

What would move the needle: design + policy

If the goal is fewer funerals, not just more arrests, pair enforcement with tech and market rules:

Intelligent Speed Assistance (ISA) or speed limiters for young drivers.

The EU now mandates ISA in all new cars (new models since 2022; all new sales since 2024). ISA can warn or even gently limit speed relative to posted limits. The U.S. has no such mandate. (road-safety-charter.ec.europa.eu)

Major automakers already ship teen speed-limit features voluntarily (proof it’s feasible). GM Teen Driver can cap speed at 85 mph and restrict acceleration; Ford MyKey can cap top speed at 65/70/75/80 mph. These are optional toggles today. Why not require them for licensed drivers under 21 (or 25)? (Chevrolet)

Insurance alignment, not just punishment.

If a family declines speed-limiting for a minor’s car, insurers could price that risk explicitly—premium multipliers—just like telematics discounts in reverse. (Insurers already surcharge for high-risk behaviors; aligning with speed-governing choices is a logical extension.)Ad accountability.

U.S. law already bans deceptive or unfair ads (FTC Act §5). The FTC has cracked down on car sales deception (junk fees, misrepresentations), and the federal CARS Rule tightens the screws. While those actions focus on pricing and claims, the authority exists to curb marketing that materially misleads about performance/safety. (Federal Reserve)Fix municipal incentives.

Cities that rely on fines for revenue can drift toward extractive enforcement. Research shows municipal dependence on fines/fees correlates with aggressive ticketing practices—without clear safety gains. That’s a policy red flag we should address alongside safety reforms. (Fines and Fees Justice Center)

“Why not just cap every car at 75 mph?”

Two truths can coexist:

We do have a tiny handful of higher-limit roads (up to 85 mph in Texas), and manufacturers cite needs like passing power and gradients. (SH 130)

Passing power → Carmakers argue cars need extra top speed and horsepower so drivers can safely pass slower vehicles on highways (for example, accelerating quickly to overtake a truck).

Gradients → They also justify extra engine power for steep hills or mountain driving, where a car might need more speed/torque to climb or merge safely.

Basically, the auto industry defends building cars that can go 120–160 mph by saying, “It’s not about racing—it’s about giving drivers enough performance for special situations like passing and hills.” In reality, though, cars don’t need anywhere near 160 mph for those situations. It’s more about marketing speed as excitement and status.

But in the real world, most driving happens on roads posted 55–75 mph. Graduated speed caps tied to driver age or license class already implemented by GM/Ford at the consumer level—are a pragmatic compromise (and unlike full governors, they can be smart/temporary). (Chevrolet)

Could you sue the auto industry for building (or hyping) fast cars?

Short answer: It’s hard—but not impossible in narrow scenarios.

Product liability (design defect): Courts generally don’t deem a car “defective” merely because it can exceed legal limits. You’d need to show an unreasonable design risk versus utility, and that a safer feasible alternative (e.g., mandated limiters) should have been adopted and would have prevented the harm. That’s an uphill battle, especially given lawful high-speed roads and the availability of consumer-activated limiters.

Unfair/Deceptive Advertising (UDAP/FTC Act §5):

If an ad materially misleads about safety or encourages illegal behavior, regulators (FTC/AGs) can act, and private plaintiffs can sometimes sue under state UDAP laws. The FTC has active enforcement history against deceptive auto marketing (though mostly pricing/claims). Extending that framework to performance/speed claims that imply safe illegal use would be novel but not inconceivable, especially with expert evidence on foreseeable misuse. (Federal Trade Commission)Negligent marketing theories: These cases exist in other product contexts but face causation and First Amendment hurdles when applied to high-performance car ads. You’d need a tight factual chain from the ad to the specific illegal racing event and harm—rare but not impossible.

Bottom line: A broad, nationwide class action against automakers for “selling fast cars” is unlikely to succeed under current U.S. law. Policy changes (NHTSA rulemaking, state laws requiring ISA for novice drivers, FTC guidance on performance advertising) are the faster lever.

A better blueprint (what we should ask lawmakers for)

Require teen/novice-driver speed-limit modes on all new vehicles sold in the U.S., with default activation for drivers under 21/25 and admin override controlled by a parent/guardian. (This mirrors existing GM/Ford tech and the EU’s move toward ISA.) (road-safety-charter.ec.europa.eu)

Tie insurance pricing to limiter adoption (opt-out is allowed, but it costs more).

Direct FTC and state AGs to scrutinize performance ads that reasonably foresee illegal use or minimize risk, using FTC Act §5 authority. (Federal Trade Commission)

De-incentivize fine farming: cap municipal reliance on traffic fine revenue and invest in engineering fixes (traffic calming, street design) proven to cut speeds. (Fines and Fees Justice Center)

If officials truly want fewer crashes…

Stop pretending we can ticket our way to safety while selling and celebrating 0–60 culture. The technology to protect kids already exists in the cars we sell. Make it standard. Make it smart. And make the incentives line up with saving lives—not padding budgets.

Sources & quick reads

NHTSA: 2023 speeding fatalities & 2024 trend update. (CrashStats)

Texas SH-130: Highest posted U.S. speed (85 mph). (SH 130)

EU ISA mandate: New models (2022) → all new sales (2024). (road-safety-charter.ec.europa.eu)

Florida street-racing penalties: §316.191, license revocation & escalating fines. (The Florida Senate)

Teen speed-limiting tech: GM Teen Driver (85-mph cap), Ford MyKey (65–80 mph). (Chevrolet)

Fines & fees dependence research: municipal revenue reliance concerns. (Fines and Fees Justice Center)

FTC authority on auto advertising & CARS Rule: deceptive/unfair practice enforcement. (Federal Trade Commission)

The Non-Youthful Youth: How the System Treats Developing Brains Like Hardened Criminals

By Truth Behind the Bars

Imagine being told you’re an adult the moment the state needs a conviction; but a child the moment it wants to punish you harshly. That is the cruel double standard at the heart of how the criminal legal system treats 18 to 21 year olds. Science shows they are still growing. The law often treats them as finished products. The result: young people who made a mistake once; often first-time offenders pushed by peers or fear. Are thrown into systems designed to punish, not rehabilitate, and their lives are ruined forever.

Brains in Progress: Why 18 is not a finished brain

Neuroscience is clear: the human brain continues to develop well into the mid-20s. The parts of the brain responsible for impulse control, planning, risk evaluation, and resisting peer pressure; primarily the prefrontal cortex are among the last to mature.

That means an 18 year old is more likely to act on impulse, misread danger, or follow peers into dangerous choices.

It also means they are far more responsive to intervention and rehabilitation than older adults. Their brains are still changeable.

So when the state demands to treat an 18-year-old exactly like a 40-year-old for sentencing purposes, it ignores these hard biological facts. It ignores science in favor of convenience.

Adults vs. Children in Court

There is no precedent in U.S. law for taking a 30-year-old with mental disabilities and saying: “We’ll try them as a juvenile offender.” So why is the reverse happening to our youth. Children with underdeveloped brains who, unlike adults, still have the capacity to grow, change, and be molded into better versions of themselves?

Adults with mental disabilities or severe mental illness are almost never downgraded to “youthful offender” status.

Instead, they may be found incompetent to stand trial (unable to understand proceedings) or not guilty by reason of insanity (unable to distinguish right from wrong at the time).

But even then, they are not reclassified as juveniles. They remain in adult systems, often in hospitals or specialized facilities.

This double standard exposes the truth: when it comes to children, the system chooses the harsher path not because it’s just, but because it’s convenient for securing convictions.

Convenient Age Lines: When the State Chooses “Adult”

The legal system draws bright lines — 16, 17, 18 — but applies them opportunistically.

If the state wants evidence or cooperation, juvenile protections or lower thresholds might be applied.

If the state wants a tougher sentence or an automatic adult prosecution, the same person is suddenly an “adult” who deserves the harshest punishments.

This isn’t about leniency for terrible acts. It’s about the inconsistent, instrumental use of “age” to get convictions and produce statistics that prosecutors can tout. Convictions mean convictions: they drive plea bargaining power, justify budgets, and feed a system rewarded by closures and sentences, not by rehabilitation.

First Offender, Forever Marked

Most of these young people are first-time offenders. Yet the system treats first-time mistakes (often one bad night, one poor decision) as proof of a permanent character defect. The consequences are catastrophic:

Mandatory long sentences or LWOP destroy any realistic chance of education, job training, or normal adult development.

Prison life hardens a person, rather than offering the treatment they needed at 18. The system transforms the “non-youthful youth” into the very thing it claims to fear.

The collateral damage extends to families, children, and entire neighborhoods.

If someone under 21 commits an unimaginably violent crime, that should be a red flag for acute mental health needs and trauma, not immediate consignment to lifelong punishment without individualized evaluation.

Constitutional and Scientific Threads: Why This Matters in Court

The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized youth as constitutionally relevant in sentencing: Roper v. Simmons (no death for juveniles), Graham v. Florida (no LWOP for non-homicide juvenile offenses), and Miller v. Alabama (no mandatory LWOP for juveniles without individualized consideration). Those rulings acknowledge that youth matters. Yet many 18 to 21 year-olds fall into a gray zone the law refuses to treat fairly.

Courts and advocates should treat youth (and near-youth) as an important factor in culpability, sentencing, and rehabilitation. The science and the Eighth Amendment’s proportionality principle demand it.

Programs, Not Permanent Punishment

When young people show risk factor: impulsivity, trauma, substance involvement. The right response is treatment and structured intervention, not lifelong isolation.

If there are evidence based programs available (mental health treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, education, family counseling), participation should be mandatory as part of disposition for young offenders with clear benchmarks and support.

When programs do not exist or are inadequate, mandatory punishment is cruel and pointless. The state must be held responsible for providing the resources it says are necessary to rehabilitate.

A single mistake especially from an impulsive, underdeveloped brain. Should not cost someone their entire future when effective alternatives exist.

The Prosecutor’s Incentive Problem

Remember: prosecutors, county budgets, and many parts of the criminal system are incentivized by convictions and case closures. That creates pressure to push young people into adult prosecutions and plea deals that look good on paper but destroy lives in practice.

Plea pressure coerces young people into giving up trial protections.

Charging decisions that escalate a juvenile or non-shooter into an adult felony murder scheme are often less about individualized culpability and more about “winning” a case.

This incentive structure demands reform, both in law and in culture.

What Real Reform Looks Like

Youth-Centered Sentencing Laws. Statutory rules requiring age-based mitigation for defendants under 25, not just under 18.

Mandatory Assessment & Treatment. Before severe sentences are imposed, require psychological assessment and, if indicated, guaranteed access to evidence-based programs.

Limit Felony Murder for Non-Killers. Require proof of major participation + reckless indifference before imposing the most severe punishments.

First-Time Offender Presumptions. For first-time offenders under 21, start with rehabilitative options unless the record shows extreme culpability.

Data & Accountability. Counties must publish data on how many young people are charged as adults, plea rates, and outcomes. Transparency changes incentives.

Final Word: A Moral and Practical Imperative

Treating 18 to 21 year-olds as forever culpable is both morally wrong and practically destructive. The science says they can change. The law, when it listens, recognizes youth matters. And the goal of a just society should be to rehabilitate when possible. Not to consign young people to a fate that makes their worst action a life sentence.

If you believe our justice system should be about fairness and second chances and not convenient convictions. Then the “non-youthful youth” must be front and center in reform efforts.

Legally Referenced Articles & Laws Supporting Youth Protections

Brain Development & Youth Immaturity

A Developmental Perspective on Serious Juvenile Crime – U.S. Courts article explaining how adolescent judgment is less mature and why laws should reflect this.

Youth Transfer to Adult Court Harms

Transfer of Juveniles to Adult Court: Effects of a Broad Policy – Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). Shows harsher outcomes, higher recidivism, and psychological harm.

Juvenile Competency Laws

National Conference of State Legislatures – overview of state laws recognizing developmental immaturity and mental disorder in evaluating juvenile competency.

Juvenile Mental Health Diversion

An Overview of Juvenile Mental Health Courts – American Bar Association, showing alternative treatment models instead of adult punishments.

Virginia Code § 16.1-280

Allows juvenile courts to commit a youth with mental illness or intellectual disability to treatment rather than prison.

North Carolina Juvenile Capacity Law

New Law on Juvenile Capacity to Proceed – explains how NC courts assess developmental immaturity and mental disorder when youth are transferred to adult court.

Federal & Florida Laws Relevant to Youth Sentencing

Federal Constitutional Protections

Fifth Amendment – Due Process & Double Jeopardy

Requires fairness in trials and prevents re-litigation of facts (Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970)).

Felony murder often convicts without proof of intent, conflicting with due process.

Sixth Amendment – Right to Jury Trial

Apprendi v. New Jersey (530 U.S. 466, 2000): Any fact increasing punishment must be found by a jury.

Felony murder imposes life/death without juries deciding intent.

Eighth Amendment – Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Roper v. Simmons (543 U.S. 551, 2005): Death penalty banned for juveniles under 18.

Graham v. Florida (560 U.S. 48, 2010): LWOP banned for juveniles in non-homicide cases.

Miller v. Alabama (567 U.S. 460, 2012): Mandatory LWOP unconstitutional for juveniles.

These cases recognize that youth matters in sentencing.

Fourteenth Amendment – Equal Protection & Substantive Due Process

Protects against arbitrary treatment.

States apply felony murder inconsistently (some abolished it, others impose LWOP), undermining equal protection.

Federal Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 2254 – Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners

Lets inmates challenge convictions in federal court if they violate the U.S. Constitution.

42 U.S.C. § 1983 – Civil Rights Actions

Allows lawsuits against state actors who deprive constitutional rights (e.g., prosecutors pursuing convictions despite due process violations).

Florida Law

Florida Stat. § 985.557 – Direct File / Juvenile Transfer

Gives prosecutors discretion to “direct file” juveniles into adult court for certain felonies.

Used aggressively in Florida, meaning many youth are automatically treated as adults.

Florida Stat. § 985.56 – Mandatory Transfer

Requires juveniles of certain ages/charges (e.g., 16–17 accused of specific felonies) to be tried in adult court.

Florida Stat. § 921.002 – Criminal Punishment Code

Sentencing code applies equally to youth tried as adults, ignoring developmental immaturity.

Independent Act Doctrine (Florida Common Law)

Recognizes that if a killing results from an independent act outside the scope of the felony, co-defendants cannot be held liable (Parker v. State, 458 So.2d 750 (Fla. 1984)).

Often overlooked in felony murder prosecutions, including Victor’s case.

Bottom line:

Federal law (Supreme Court rulings + Amendments) clearly acknowledges youth are different.

Florida statutes, on the other hand, empower prosecutors to treat juveniles as adults. While ignoring brain science and constitutional principles.

The History of Felony Murder: An Archaic and Unjust Law

By Truth Behind the Bars

The felony murder rule is one of the most controversial doctrines in American criminal law. It dates back to English common law of the 1500s–1600s, when society believed that anyone involved in a crime should be punished for every consequence, even unintended ones. Back then, the law was brutally simple: “If death results from a felony, all are guilty of murder.”

But centuries later, this idea is outdated, unfair, and dangerous. Modern justice systems around the world have abolished or limited felony murder because it punishes people not for their actions, but for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Why It’s Unfair

The felony murder rule means that a person can be sentenced to life in prison EVEN DEATH! for a killing they neither committed nor intended.

You don’t have to pull the trigger.

You don’t have to know it’s going to happen.

In some cases, you don’t even have to be physically present.

It replaces the constitutional principle of individual culpability with a blanket of guilt.

How States Handle Felony Murder Today

Felony murder is not applied uniformly. Some states have recognized its unfairness and restricted or abolished it.

Abolished: Hawaii, Kentucky, Michigan, and Massachusetts have done away with it.

Restricted: States like California (Senate Bill 1437, 2019) limit it to major participants who acted with reckless indifference to human life.

Broad Use (like Florida): Still apply it harshly, even to non-shooters, getaway drivers, or people who had left the scene.

This patchwork proves its weakness: if justice depends on what state you’re in, then justice isn’t justice at all.

What Triggers Felony Murder?

A person can face felony murder for:

Being present - during a felony where a death occurs (robbery, burglary, arson, drug deal).

Being an accomplice - even if unarmed and passive.

Providing minor aid - like lending a car (Ryan Holle) or acting as lookout.

Not even being there - simply planning or associating with people who commit the felony.

Deaths caused by third parties - even if a police officer or a victim causes the death.

Why It’s Unconstitutional in Spirit

Eighth Amendment → Disproportionate punishment (life without parole for someone who never killed).

Due Process (14th Amendment) → No fair assessment of individual culpability.

Universal Human Rights → Global trend is to abolish collective punishment.

Independent Act Doctrine

Florida law recognizes the Independent Act Doctrine: if one participant in a felony commits an act outside the scope of the original plan, it is an independent act that breaks the chain of liability.

Example: If the robbery has ended and a co-felon commits a new, separate crime, others cannot be held responsible.

In Victor’s case, once the store owner pursued and escalated the situation, the chain of causation legally broke. Yet the felony murder charge ignored this doctrine.

Felony Murder Status by State (2025 Overview)

The Absurdity of Felony Murder: Sentenced for Killings They Didn’t Commit

Ryan Holle (Florida, 2003)

Ryan lent his roommate his car in 2003, knowing his friends were going to burglarize a house.

He stayed home, never went to the scene, never held a weapon, never saw the victim.

During the burglary, someone else killed the homeowner.

Ryan was convicted of first-degree felony murder and sentenced to life without parole.

His case shows the extreme injustice: punished as a murderer for not stopping a crime he wasn’t present at.

Citation: Holle v. State, 159 So.3d 402 (Fla. 1st DCA 2015).

Victor Salastier Diaz Estevez (Florida, 2007)

Victor was not the shooter, and in his first trial (2007) the jury signaled his lower culpability.

The event that led to death wasn’t even part of the robbery: the store owner chased after the suspects, armed, while on the phone with 911.

Under Florida’s Independent Act Doctrine, once a felony has ended and a third party (like a store owner) starts a new, independent chain of events, any resulting death cannot be pinned on the original suspects.

Despite this, prosecutors relitigated him through multiple trials until they secured a felony murder conviction — ignoring the fact that legally, the killing had broken away from the original event.

Citation: Diaz Estevez v. State, Case Nos. 4D10-1865 & 4D11-1367 (Fla. 4th DCA 2011).

Emmanuel Mendoza (California, 1997)

Emmanuel Mendoza helped lure a robbery victim to a meeting place where another man carried a gun.

He did not fire the weapon, did not plan the killing, and did not intend for anyone to die.

During the robbery, the armed accomplice shot and killed the victim.

Mendoza was convicted of felony murder with “special circumstances.”

He was sentenced to life without parole.

Citation: People v. Mendoza, 18 Cal.4th 1114 (Cal. Sup. Ct. 1998).

Derek Lee (Pennsylvania, 2014)

Derek Lee participated in a robbery where his co-defendant shot and killed someone.

Lee was not the shooter and did not fire a weapon.

Pennsylvania law mandates life without parole for second-degree murder (felony murder).

Lee was automatically sentenced to LWOP — no discretion given.

His case is now part of a constitutional challenge in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

Citation: Commonwealth v. Derek Lee, No. 14 WAP 2023 (Pa. Supreme Court, pending 2024).

Lakeith Smith (Alabama, 2015)

At age 15, Lakeith Smith was involved in a series of burglaries with friends.

During one of the burglaries, police shot and killed one of his co-defendants.

Although Smith never fired a shot, he was charged with felony murder for his friend’s death.

In 2018, he was sentenced to 55 years in prison (30 years for felony murder, plus burglary sentences).

His case drew national attention as an example of how the felony murder rule can punish teenagers harshly when police are the ones who pull the trigger.

Citation: State v. Smith, Montgomery County Circuit Court, Alabama (2018).

Conclusion

The felony murder rule is a legal relic — rooted in centuries-old common law, but incompatible with modern justice. It punishes people not for what they did, but for what others did.

Cases like Ryan Holle’s and Victor’s show how devastating and illogical this rule is. In a country that claims to value fairness and proportional justice, felony murder remains one of the most archaic, unlawful, and unjust doctrines still on the books.

It’s time for reform — because being in the wrong place at the wrong time should not equal life in prison.

Federal Constitutional Protections That Undermine the Felony Murder Doctrine

The felony murder rule collides with fundamental constitutional principles. U.S. Supreme Court precedent and federal statutes provide strong grounds to challenge its fairness, proportionality, and legality.

1. Fifth Amendment – Double Jeopardy & Due Process

Double Jeopardy Clause: Prevents relitigation of facts already decided (Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970)).

Due Process Clause: Requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt of individual culpability, not guilt by association.

Relevance: Felony murder often convicts defendants of murder despite acquittals or without proof they killed or intended to kill.

2. Sixth Amendment – Right to a Jury Trial & Counsel

*Apprendi v. New Jersey (2000)**: Any fact that increases punishment must be found by a jury.

Relevance: Felony murder statutes impose life or death sentences without a jury finding intent to kill, violating the Sixth Amendment.

3. Eighth Amendment – Cruel and Unusual Punishment

SCOTUS has struck down extreme sentences for juveniles and non-killers:

*Enmund v. Florida (1982)**: Death penalty unconstitutional for a non-shooter getaway driver.

*Tison v. Arizona (1987)**: Only “major participants” acting with reckless indifference may face capital punishment.

*Miller v. Alabama (2012)**: Mandatory LWOP for juveniles unconstitutional.

Relevance: Life without parole for non-shooters, minors, or minimal participants is disproportionate and violates evolving standards of decency.

4. Fourteenth Amendment – Due Process & Equal Protection

Due Process: Felony murder violates substantive due process principles because it punishes without proof of mens rea (intent).

Equal Protection: States treat felony murder differently (some abolished it, others mandate LWOP), creating disparate outcomes between states — some allow life for minor involvement, others don’t even have felony murder. Producing arbitrary, unequal outcomes.

5. Federal Statutory Hooks

28 U.S.C. § 2254 – Federal Habeas Corpus: Permits state prisoners to challenge convictions in federal court when constitutional rights are violated.

42 U.S.C. § 1983 – Civil Rights Actions: Enables lawsuits against state actors who violate constitutional rights during felony murder prosecutions.

International Treaties / Human Rights (as persuasive authority): ICCPR (International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights) — U.S. is a party, and it prohibits disproportionate punishment. Not binding in habeas, but persuasive in reform advocacy.

Federal Case Law Anchors

Ashe v. Swenson (1970) → Collateral estoppel is part of the Fifth Amendment; facts once decided can’t be re-litigated.

Enmund v. Florida (1982) → No death penalty for minor participant/non-killer.

Tison v. Arizona (1987) → Set “major participant + reckless indifference” threshold.

Kennedy v. Louisiana (2008) → Proportionality principle; death can’t be imposed where victim wasn’t killed.

Miller v. Alabama (2012) → Juveniles can’t face mandatory LWOP, even for felony murder.

Graham v. Florida (2010) → LWOP unconstitutional for juveniles in non-homicide cases; shows proportionality standards.

Conclusion:

The felony murder rule is out of step with constitutional protections designed to ensure fairness, proportionality, and individualized justice. These federal safeguards form the backbone of challenges against convictions that punish people for killings they did not commit.

The State vs. The Individual

By Truth Behind the Bars

In the United States, crimes are not treated as private disputes between two people — they are considered offenses against society as a whole. That’s why criminal cases are filed as “State of Florida vs. [Defendant]” or “People vs. [Defendant].”

Why the State Prosecutes (Even if the Family Doesn’t Want To)

Once a crime is reported, it is the State’s decision — not the victim’s — whether to press charges.

This authority comes from the State’s police power, rooted in the 10th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which gives states the power to create and enforce criminal laws to protect public safety.

Florida law (see Florida Statutes § 27.02 and § 27.34) places this responsibility in the hands of the State Attorney’s Office, not the victim or their family.

Courts have repeatedly held that “the right to prosecute belongs to the State, not to private citizens” — meaning even if a victim forgives or refuses to testify, the State can and will move forward.

The Real Focus: Convictions, Not Truth

Prosecutors are judged on their conviction rates, not on uncovering the truth. Conviction is treated as success — even if the case rests on shaky evidence or questionable legal tactics. The family of a victim may want mercy, forgiveness, or even no charges at all, but the State’s priority is to “win” in court.

A Rigged Playing Field

Defendants who cannot afford private counsel are given a court-appointed attorney — often from the Public Defender’s Office, which is also funded and regulated by the State. This creates a troubling imbalance:

The State Attorney prosecutes the case.

The Public Defender, technically a State employee, defends the case.

The Judge, a State officer, presides.

It’s a system where every actor is tied to the State — and the one person who is not, the defendant, is left isolated.

Suggested Reference Points you can cite on your page:

U.S. Const. Amend. X (police powers of the states).

Florida Stat. § 27.02 – Duties of the state attorney (charging & prosecuting).

Florida Stat. § 27.34 – State attorneys responsible for prosecuting all crimes.

Case law: State v. Cain, 381 So.2d 1361 (Fla. 1980) – confirms that prosecution is a State function, not dependent on a victim’s choice.

In the United States, crimes are not treated as private disputes between two people — they are considered offenses against society as a whole. That’s why criminal cases are filed as “State of Florida vs. [Defendant]” or “People vs. [Defendant].”

Why the State Prosecutes (Even if the Family Doesn’t Want To)

Once a crime is reported, it is the State’s decision — not the victim’s — whether to press charges.

This authority comes from the State’s police power, rooted in the 10th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which gives states the power to create and enforce criminal laws to protect public safety.

Florida law (see Florida Statutes § 27.02 and § 27.34) places this responsibility in the hands of the State Attorney’s Office, not the victim or their family.

Courts have repeatedly held that “the right to prosecute belongs to the State, not to private citizens” — meaning even if a victim forgives or refuses to testify, the State can and will move forward.

The Real Focus: Convictions, Not Truth

Prosecutors are judged on their conviction rates, not on uncovering the truth. Conviction is treated as success — even if the case rests on shaky evidence or questionable legal tactics. The family of a victim may want mercy, forgiveness, or even no charges at all, but the State’s priority is to “win” in court.

A Rigged Playing Field

Defendants who cannot afford private counsel are given a court-appointed attorney — often from the Public Defender’s Office, which is also funded and regulated by the State. This creates a troubling imbalance:

The State Attorney prosecutes the case.

The Public Defender, technically a State employee, defends the case.

The Judge, a State officer, presides.

It’s a system where every actor is tied to the State — and the one person who is not, the defendant, is left isolated.

Suggested Reference Points you can cite on your page:

U.S. Const. Amend. X (police powers of the states).

Florida Stat. § 27.02 – Duties of the state attorney (charging & prosecuting).

Florida Stat. § 27.34 – State attorneys responsible for prosecuting all crimes.

Case law: State v. Cain, 381 So.2d 1361 (Fla. 1980) – confirms that prosecution is a State function, not dependent on a victim’s choice.